3.4.1 2-dimensional grids with nested loops¶

A common computational pattern in PDC applications is the use of a structured grid to represent, or model a real-life situation in nature. This computational patter is listed in the second column from the left in the patterns diagram in Chapter 1 of this book. At the heart of these computations are 2-dimensional arrays, or grids.

In this example, we will create the 2-dimensional grid of width w and length l as a flattened array in this manner:

// a flattened 2D grid of doubles of size width x length

int arraySize = (width) * (length);

size_t bytes = arraySize * sizeof(double);

double *grid = (double *)malloc(bytes);

In this scheme, the width is the number of columns and the length is the number of rows. The command line arguments enable you to change these values (they replace the number of repetitions in the previous examples):

-t indicates number of threads to use.

-w indicates the width of the 2D grid (default is 8).

-l indicates the length of the 2D grid (default is 8).

-c indicates that a fixed seed will be used, resulting in the same

stream of numbers each time this is run.

-d indicates whether the trng generator will dole out numbers in

block or in leapfrog fashion. (default is block).

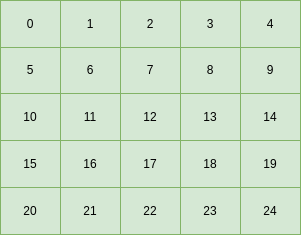

Another change you might note here is that we have changed the default method of splitting up the stream of random numbers to blocks rather than leapfrog. We’ve done this because this method naturally enables better use of cache memory because the grid can be naturally accessed in row-major order in nested loops: row by row, column by column. Let’s examine this in more detail. A 5 x 5 grid, would have indices in the flattened 1D array like this:

A natural way to traverse this flattened 2D grid in a sequential fashion, placing random numbers in it, is as follows:

int i, j;

double randN;

for (i = 0; i < l; i++) { // row by row

for (j = 0; j < w; j++) { // column by column

randN = uni(RNengine);

int id = i * w + j; // flattened 2D index

grid[id] = randN;

}

}

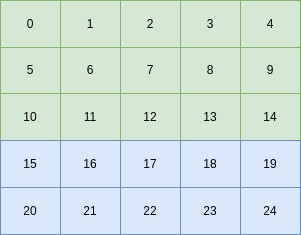

Now let’s suppose that we want to do this in parallel by having each thread work on a certain number of rows. With 2 threads we can imagine a decomposition like this, with the green cells for thread 0 and the blue cells for thread 1:

The code for populating each row is found in the function called populateRows in the code block below (line 152 in the code you can run later). Note that this function is executed independently by each thread. Here it is pulled out so that you can compare it to the sequential version above:

// Traverse row by row, knowing the start and end row for this thread.

// PREREQUISITE: block splitting of the random numbers between threads is being used.

//

void populateRows(double *grid, int w, int l, trng::yarn2 RNengine, trng::uniform01_dist<> uni,

int startRow, int endRow, int tid) {

int i, j;

double randN;

for (i = startRow; i < endRow; i++) {

for (j = 0; j < w; j++) {

randN = uni(RNengine); // inside loop

int id = i * w + j; // flattened 2D index

if (w <= 8 && l <= 8) {// for debugging, print the random number and indices

printf("%0.3f %2d %2d %d %d |\n", randN, id, tid, i, j);

}

grid[id] = randN;

}

}

}

As you can see, the difference in the nested loops between the sequential and the parallel version is that each thread will work on a particular set of rows, generating random numbers from a block that was assigned to it. This is done with a new function called getStartStopRow (shown below) that each thread executes. The starting point for a block of random numbers to be used by a thread is created as follows inside the function createNewGrid (line 132 in the code you can run below):

// Use block splitting to partition random numbers among threads

getStartStopRow(tid, numThreads, l, &startRow, &endRow); // enables unequal blocks per thread

long unsigned int numsToSkip = (long unsigned int)startRow * (long unsigned int)w;

RNengine.jump(numsToSkip);

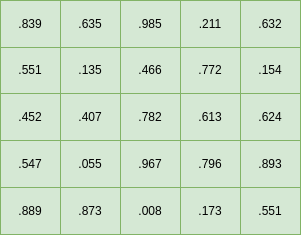

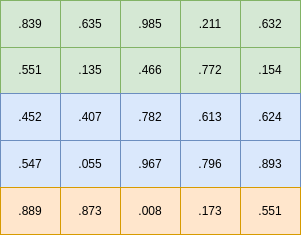

Let’s visualize this. A stream or random numbers between 0 and 1.0 can be generated and placed row-by-row, column-by column into a 5x5 grid as follows:

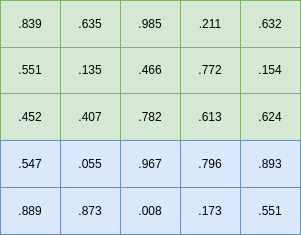

If we use the code above with 2 threads, each thread will use the numbers in blocks of rows like this:

Using 3 threads will split the stream into blocks of rows like this:

TO DO:

Try the code below by using -t values of 1, 2, and 3. Does it match the images above?

Warning

If you try sizes larger than 7 x 7, the printing of the resulting matrix gets cut off. For arrays beyond 8x8, you can see them if you comment line 96 and 99 so that the grid prints out. However, the most you can set to see the whole resulting array is width of 18 and length of 14.

The bottom line¶

What we can observe from this example is that a 2D grid, flattened into a 1D array of contiguous values in memory, can be populated using multiple threads by having the nested loop that traverses the array row-by-row split into segments of rows. The block-splitting mechanism of the trng parallel random number library can also be used to segment the stream of random numbers in a similar fashion.

It is also possible to use trng’s leapfrogging version of assigning numbers from the stream of random numbers to each thread, but unfortunately the more natural way of combining this with the nested loop is to have threads work on columns of the grid. This is less efficient for cache memory use. You can try it to see it in action. It uses more numbers of the random stream by skipping some of them. Why this is happening is beyond the scope of the purpose of this chapter.

Calculating the start and stop rows per thread¶

The following code shows the function getStartStopRow used in the example above. Study it to see how the values are determined for a flattened 2D grid of particular length l.