4.1 MapReduce¶

Modern Internet search engines must process truly enormous amounts of data. For example, Google search gathers information from hundreds of billions of web pages, and produces an index of every word that appears on every web page, requiring over 100,000,000,000,000,000 (10^17) bytes of data! How is it possible to perform such a huge computation in a reasonable amount of time?

Distributed computing using a MapReduce strategy is a common approach to performing such “big data” computations. By using Map-Reduce on clusters of thousands of powerful networked computers, the work can be divided up among those computers in order to complete in hours what would take a single computer years to perform. Those computers are typically part of a cloud computing service provided by companies such as Amazon, Google, or Microsoft. The open-source MapReduce framework Hadoop, used by over half of Fortune 500 companies, is designed for reliability, making it possible to continue a computation with minimal delay even if computers or networks crash during the job.

In this section, we will describe the MapReduce programming model and explore how to create programs capable of true big-data computations.

4.1.1 The MapReduce programming strategy¶

A MapReduce framework such as Hadoop provides most of the details of data handling, such as dividing enormous data sets up into splits that are small enough for one computer to process, managing the low-level input and output operations, replicating the data to prevent data loss if one or more computers or networks crash, and automatically recovering from such crashes during a big-data computation. Thus, an application programmer never writes the “main program” for a MapReduce computation, which is unlike other programs in this book. Instead, the programmer writes two functions that determine how the framework should process the data, called the mapper and the reducer.

The mapper function operates on the input data and generates key-value pairs that represent some information of interest from that input.

For example, if we are interested in finding all occurrences of words in a data set of web pages, a mapper function might operate on one line of a web page and produce a key-value pair for each word in that line, where the key is that word and the value is the name of that web page, e.g., (“the”, “mysite/index.html”).

The reducer function acts on all key-value pairs produced by mappers that have the same key and produces other key-value pairs that distill or summarize the interesting information in those input pairs.

For example, if we’re interested in how frequently each word appears in each web page, and the input key-value pairs have the form (“the”, “mysite/index.html”), then a reducer might produce key-value pairs of the form (“the mysite/index.html”, “28”) where 28 is the count of input pairs matching that web-page value.

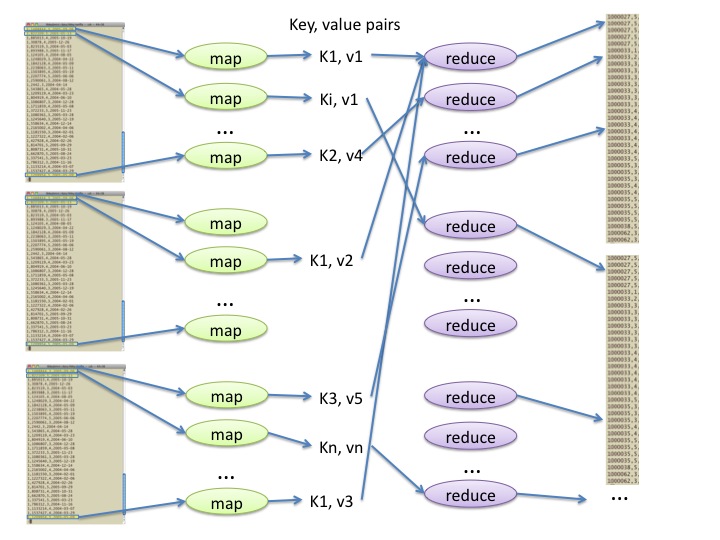

Figure 1 shows the effects of calling mappers on each line of each split of input data, then calling reducers on the various key-value pairs produced by those mappers.

Figure 1: Illustration of calling a mapper function named map() many times in parallel and passing the results of those calls to calls of a reducer function named reduce().¶

As Figure 1 shows, each reducer call handles all the key-value pairs for a particular key. For instance, in our example above of counting the frequencies of words within web pages, if the key K1 in the diagram is the word "the" and the values v1, v2, and v3 are the names of three different web pages such as "mysite/index.html" and two others, then the top reducer would handle all three of those pairs (plus any other unshown pairs that have the key "the").

By writing the mapper and reducer functions for a MapReduce framework, a programmer specifies what computation should be performed on a potentially gigantic data set. This modest two-function programming strategy provides a surprising amount of algorithmic control for big-data computations. Here are some examples, starting with the word-frequency example above:

- Goal

Count frequencies of all words in all web pages in a data set of web pages

- mapper

Read one line of input from a web page wpname, and produce a key-value pair ( “w”, “wpname”) for each word w that appears on that line

- reducer

Receive all key-value pairs (“w”, “wpname”) for a given word w, and produce one key-value pair (“w wpname”, “ct”) for each web page wpname, where ct is the number of input pairs with value wpname.

- Goal

For every word found in a data set of web pages, produce a list of all line numbers of web pages containing that word.

- mapper

Read one line of input from a web page wpname, and produce a key-value pair (“w”, “ln wpname”) for each word w that appears on that line, where ln is the line number within wpname that was read

- reducer

Receive all key-value pairs (“w”, “ln wpname”) for a given word w, and produce one key-value pair (“w wpname”, “ln1 ln2 ln3 …”) for each web page wpname, where lnN is the N th value of ln among input pairs with values ln wpname

- Goal

Find the average rating for each movie in a data set of movie ratings.

- mapper

Read one movie rating, consisting of an integer movie id mid, an integer rating r from 0 to 5, and other information such as reviewer and date. Produce a pair (“mid”, “r”)

- reducer

Receive all key-value pairs (“mid”, “r”) for a given movie id mid, and produce a pair (“mid”, “ave”) where ave is the average value of r among all those input pairs.

Besides providing the code for a mapper and a reducer, a MapReduce programmer must also enter configuration options for the framework, e.g., specifying where to find the data set, what type of data that data set contains, where to store the results, perhaps indicating how to split the data set, etc.

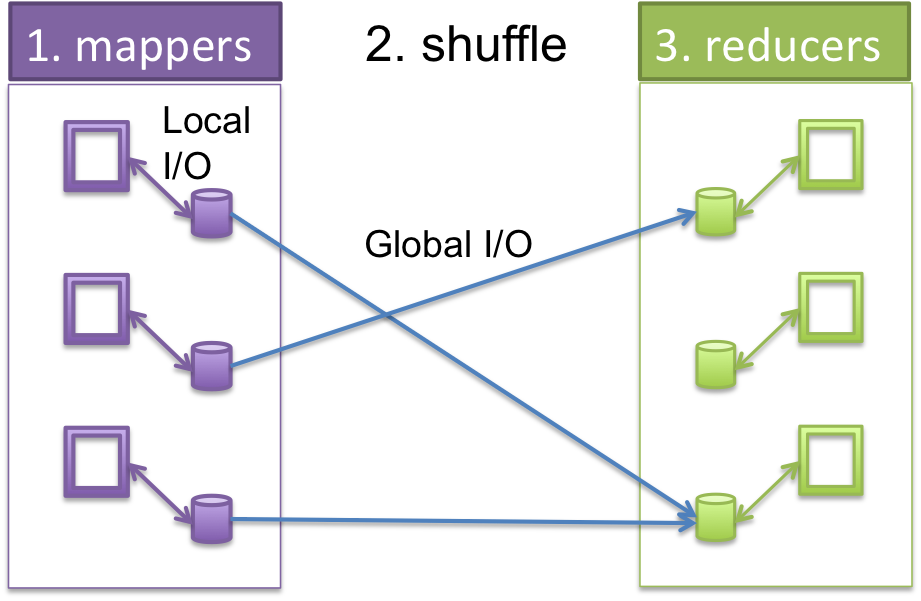

Note that a MapReduce framework also provides an automated sorting of all key-value pairs produced by the mapper calls, after all mapper calls have completed and before any reducer calls begin. The framework needs this automated sorting operation, called the shuffle, in order to collect all key-value pairs having the same key for calls of the reducer. For big data jobs requiring thousands of networked computers, shuffling may be a complex intensive computation of its own, another service that a MapReduce framework provides automatically - and that we don’t need to program ourselves!

Finally, a MapReduce framework also implements crucial performance features. For example, retrieving data from a local disk is much faster than retrieving that data over a network, so a framework insures that mapper calls occur on a computer whose local disks contain their input splits, and that reducer calls likewise occur on computers that locally contain the data those reducers need. Only shuffling requires global movement of data over a network, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2: How each computer in a cluster breaks up the work and runs mappers locally, then shuffles the key-value pair results by key and sends the results for each key to other computers who run reducers.¶

Patterns and fault tolerance¶

MapReduce frameworks represent implement several parallel programming patterns.

The Data Parallel pattern, in which multiple portions of data are processed simultaneously on multiple processors (CPUs). This occurs when multiple splits of data are handled by mappers called on different computers.

The Map-Reduce pattern, in which data processing is accomplished using a mapper function and a reducer function as described above.

The Map-Reduce pattern for problem solving was pioneered decades ago in functional programming languages such as LISP or Scheme, generally without parallelism. Google adapted the map-reduce programming model to function efficiently on large clusters of computers to process vast amounts of data–for example, Google’s selection of the entire web (Dean and Ghemawat,2004).

Our discussion is based on the MapReduce framework Hadoop, an open-source implementation of the Apache Foundation, which was started primarily by Yahoo!. Hadoop is not the only MapReduce framework: before Hadoop, Google implemented a proprietary framework of their own described in the paper above; some other implementations are intended for smaller-scale computations that fit on a single computer.

Hadoop’s ability to complete a correct computation even when there are crashes is an example of fault tolerance. We already mentioned several fault-tolerance features in Hadoop, including replication of the data set and automated continuation of a large computation. Other fault-tolerance features include guaranteeing that copies of data splits reside on different computers, and the computational design where all mappers complete before any of the shuffle, and all of the shuffle completes before any reducers begin (this guards against errors due to partially completed stages of computation).

4.1.2 WebMapReduce, a simplified interface for MapReduce computing¶

To get some hands-on experience with MapReduce computing, we will use a web-based interface called WebMapReduce (WMR) that makes Hadoop convenient enough for beginning computer science courses to use. Although WMR can be set up to launch a true big-data computation involving thousands of computers, we will focus on small jobs in order to get familiar with MapReduce programming.

You should access WebMapReduce now and register for a login by going to this URL on your web browser:

http://cumulus.cs.stolaf.edu/wmr/

Choose the link at the very upper right of this page that says ‘Register’. Use your email address as your login name, and provide the other information asked for. You choose your own password, so that you can remember it and have control of your account.

Note: To complete your registration, you will need a registration key from your instructor.

For later reference, you may want to check this documentation for WMR.

For this activity, you should be able to follow along with the instructions below and determine how to use WMR.

4.1.2.1 An example of map-reduce computing with WMR: counting words¶

To program with map-reduce, you must first decide how to use mappers and reducers in order to accomplish your computational goal. The mapper function should take a line of input and decompose it somehow into key-value pairs; then the reducer should somehow condense or analyze all the key-value pairs having a common key, and produce a desired result.

The following example is small to illustrate how the process works. In realistic applications, which you will try later in this activity and in homework, the input data is much larger (several to hundreds of Gigabytes) and is stored in the Hadoop system. You will go through the following exercise first to ensure that the code is working and that you understand how it works. Then you can move on to bigger files. This is the process you should go through when doing this kind of coding: work on small amounts of data first to ensure correctness of your code, then try larger amounts of data.

As an example, consider the problem of counting how frequently each word appears in a collection of text data. For example, if the input data in a file is:

One fish, Two fish,

Red Fish, Blue fish.

Blue Fish, Two Fish.

then the output should be:

Blue 2

One 1

Red 1

Two 2

fish, 2

Fish, 2

fish. 1

Fish. 1

As this output indicates, we did not make any attempt to trim punctuation characters in this first example. Nor did we consider that some words in our text might be capatalized and some may not. We will also not do so as we practice using WebMapReduce with the initial functions described below. However, you can consider adding punctuation removal and lowercase conversion to your mapper code as you work through the example.

Note

The WebMapReduce system will sort the words according to the ASCII codes of the characters within words.

As we shall see, each word and its count will be separated by a

TABcharacter in WebMapReduce output.

What follows is a plan for the mapper and reducer functions.

Map-reduce plan¶

In WMR, mapper functions work simultaneously on lines of input from files, where a line ends with a newline charater. The mapper will produce one key-value pair (w, count) for each and every word encountered in the input line that it is working on.

Thus, on the above input, three mappers working together, one on each line, could emit the following combined output:

One 1

fish, 1

fish, 1

Two 1

Red 1

Fish, 1

Blue 1

fish. 1

Blue 1

Fish, 1

Two 1

Fish. 1

The reducers will compute the sum of all the count values for a

given word w, then produce the key-value pair (w, sum). Each pair appears as w TAB sum in the output.

In this example, we can envision a reducer for each distinct word found by the three mappers, where the reducer gets a list of single counts per occurance of the word that a mapper found, looking like this:

One [1]

fish, [1, 1]

Two [1,1]

Red [1]

Fish, [1,1]

Blue [1,1]

fish. [1]

Fish. [1]

Each reducer works on one of the pairs of data shown above, and the system handles creating words with the lists of counts as shown above.

One System, Many Languages¶

In map-reduce framework systems in general and in WMR specifically, you can use one of several programming languages to code your mapper and reducer functions. The following table contains links to solutions in several languages for the word-count solution we describe below.

Language |

Mapper function code |

Reducer function code |

|---|---|---|

Python |

||

C++ |

||

C |

||

Java |

The mapper function¶

Each mapper process is receiving a line from a file as its key initially when the process starts (the value is empty, or null). You write one mapper function to be executed by those prcesses on any given line from any particular file. Our goal is to have the mapper output a new (key, value) containing a word found and the number one, as shown for the three-mapper example above.

Here is psedocode for what a typical mapper might accomplish:

# key is a single line from a file.

#

# value is empty in this case, since this is the first mapper function

# we are applying.

#

function mapper(key, value)

1) Take the key argument to this function, which is the line of text,

and split it on whitespace

2) For every word resulting from the split key line:

'emit' a pair (word, "1") to the system for the reducers to handle

Here is a Python3 mapper function for accomplishing this task using the WMR system. We include the feature of stripping away puncuation characters from the input and converting each word found to lowercase.

1 2 3 4 5 | def mapper(key, value):

words=key.split()

for word in words:

Wmr.emit(word, '1')

|

This code is available for download in the table above, as are versions in other languages. Note that in each language you will need to know how to specify the (key, value) pair to emit to the system for the reducers to process. We see this for Python in line 4 above.

The reducer function¶

In the system, there will be reducer processes to handle each word ‘key’ that was emitted by various mappers. You write reducer code as if your reducer function is getting one word key and a container of counts, where each count came from a different mapper that was working on a different line of a file or files. In this simplest example, each count is a ‘1’, each of which will be summed together by the reducer handling the particular word as a key.

Pseudocode for a reducer for this problem looks like this:

# key is a single word, values is a 'container' of counts that were

# gathered by the system from every mapper

#

function reducer(key, values)

set a sum accumulator to zero

for each count in values

accumulate the sum by adding count to it

'emit' the (key, sum) pair

A reducer function for solving the word-count problem in Python is

1 2 3 4 5 6 | def reducer(key, iter):

sum = 0

for s in iter:

sum = sum + int(s)

Wmr.emit(key, str(sum))

|

This code is also available in the table above containing versions in several languages.

The function reducer() is called once for each distinct key

that appears among the key-value pairs emitted by the mapper, and

that call processes all of the key-value pairs that use that key.

On line 1, the two parameters that are arguments of reducer()

are that one distinct key and a Python3 iterator (similar to a

list, but not quite) called values, which provides access to

all the values for that key. Iterators in Python3 are designed for

for loops- note in line 3 that we can simply ask for each value

one at a time from the set of values held by the iterator.

Rationale: WMR reducer() functions use iterators instead of

lists because the number of values may be very large in the case of

large data. For example, there would be billions of occurrences of

the word “the” if our data consisted of all pages on the web. When

there are a lot of key-value pairs, it is more efficient to

dispense pairs one at a time through an iterator than to create a

gigantic complete list and hold that list in main memory; also, an

enormous list may overfill main memory.

The reducer() function adds up all the counts that appear in

key-value pairs for the key that appears as reducer()’s

first argument (recall these come from separate mappers). Each

count provided by the iterator values is a string, so in line 4

we must first convert it to an integer before adding it to the

running total sum.

The method Wmr.emit() is used to produce key-value pairs as

output from the mapper. This time, only one pair is emitted,

consisting of the word being counted and sum, which holds the

number of times that word appeared in all of the original data.

4.1.2.2 Running the example code on WebMapReduce¶

To run WMR with this combination of data, mapper, and reducer, carry out the following steps.

In a browser, visit the WMR site at (if you don’t already have it open from registering):

After you have registered, you can use your email address and password to login. After successfully logging in, you are taken to the WMR page where you can complete your work.

Enter a job name (perhaps involving your username, for uniqueness; avoid spaces in the job name and make sure that it is more than 4 characters long).

Choose the language that you wish to try.

For now, you can leave the number of map tasks and reduce tasks blank. This will let the system decide this for itself. You can also leave the default choice of sorting alphabetically.

Enter the input data, e.g., the fish lines above. You can use the Direct Input option and enter that data in the text box provided.

Enter the mapper. It’s probably best to use se the ``Upload” option and navigate to a file that contains the mapper, which you have entered using an editor (this is more convenient for repeated runs). Or you can use the file we provided in a table of links above.

Beware: cutting and pasting your code from a pdf file or a web page or typing it into the `’direct’ entry box for Python code is a bit problematic, because the needed tabs in the code might not be preserved (although using spaces should work). Check that the appropriate radio button is clicked to indicate the source option you’re actually using.

Also enter the reducer. Again, it’s easier to use the file provided with a link in the table above.

Click on the submit button.

A page should appear indicating that the job started successfully. This page will refresh itself as it is working on the job to show you progress.

Once the job runs to completion, you should see a Job Complete page. This page will include your output. If you used the fish input, your output should match the illustration above, except that the punctuation should also be taken care of.

If something doesn’t work as described here, the following section may help with troubleshooting. Read it next in any case so that you know what you can do when you work on your own new examples.

4.1.3 More about using WMR¶

Using WMR and its test mode¶

Here is some information about developing WMR map-reduce programs,and what to do if something goes wrong with your WMR job.

First, a reminder:

At present, the WMR interface does not automatically reset radio buttons for you when you upload a file or use Distributed FileSystem data generated from a prior map-reduce run. Always check to see that the radio buttons select the data, mapper, and reducer resources you intend.

You can test your mapper alone without using your reducer by using the identity reducer, which simply emits the same key-value pairs that it receives. Here is an implementation of the identity reducer for Python:

As an example, if you use the word-count mapper with the identity reducer, then the “fish” data above should produce the following output:

Blue 1 Blue 1 fish, 1 fish, 1 fish. 1 Fish, 1 Fish, 1 Fish. 1 One 1 Red 1 Two 1 Two 1Observe that the output is sorted, due to the shuffling step. However, this does show all the key-value pairs that result from the word-count mapper.

Likewise, you can test your reducer alone without using your mapper by substituting the

identity mapper, which simply copies key-value pairs from lines of input data. Here is an implementation of the identity mapper in Python:1 2 3

def mapper(key, value): Wmr.emit(key, value)

Here are identity mappers and reducers for some languages.

Language |

Mapper function code |

Reducer function code |

|---|---|---|

Python |

||

C++ |

||

Java |

For example, you could enter a small amount of input data that you expect your mapper to produce, such as the

TAB-separated key-value pairs listed above from using the identity reducer. If you then use the identity mapperidmapper.pywith the word-count reducerwcreducer.pyyou should get the following output, which we would expect from each stage working:Blue 2 fish, 2 fish. 1 Fish, 2 Fish. 1 One 1 Red 1 Two 2Note: Use a

TABcharacter to separate the key and value in the input lines above. To keep a test case around, it is easier to enter your data in an editor, then cut and paste to enter that data in the text box. Alternatively, you can “Upload” a file that contains the data.

Unfortunately, the current WMR system does not provide very useful error messages in many cases. For example, if there’s an error in your Python code, no clue about that error can be passed along in the current system.

In order to test or debug a mapper and reducer, you can use the

TestButton at the bottom of the WMR web page. The job output from this choice shows you what both the mapper and reducer emitted, which can be helpful for debugging your code.Note

Do not use

Testfor large data, but only to debug your mappers and reducers. This option does not use cluster computing, so it cannot handle large data.

Additional Notes¶

It is possible that input data files to mappers may be treated differently than as described in the above example. For example, a mapper function might be used as a second pass by operating on the reducer results from a previous map-reduce cycle. Or the data may be formatted differently than a text file from a novel or poem. These notes pertain to those cases.

In WMR, each line of data is treated as a key-value pair of

strings, where the key consists of all characters before the first

TAB character in that line, and the value consists of all

characters after that first TAB character. Each call of

mapper() operates on one line and that function’s two arguments

are the key and value from that line.

If there are multiple TAB characters in a line, all TAB

characters after the first remain as part of the value argument

of mapper().

If there are no TAB characters in a data line (as is the case

with all of our fish lines above), an empty string is created for

the value and the entire line’s content is treated as the key. This

is why the key is split in the mapper shown above.

4.1.4 WMR Exercises¶

A. Next Steps with word counting¶

In WMR, you can choose to use your own input data files. Try choosing to ‘browse’ for a file, and using this

mobydick.txtas file input.You have likely noticed that capitalized words are treated separately from lowercase words. Change your mapper to also convert each word to lowercase before checking whether it is in the dictionary.

Also remove punctuation from each word after splitting the line (so all the ‘fish’ variations get counted together).

There are a large number of files of books from Project Gutenberg available on the Hadoop system underlying WebMapReduce. First start by trying this book as an input file by choosing ‘Cluster Path’ as Input in WMR and typing one of these into the text box:

/shared/gutenberg/WarAndPeace.txt/shared/gutenberg/CompleteShakespeare.txt/shared/gutenberg/AnnaKarenina.txtThese books have many lines of text with ‘newline’ characters at the end of each line. Each of you mapper functions works on one line. Try one of these.

B. Creating a search index¶

Consider our original motivating example for MapReduce, namely creating a search engine. A web-search engine must perform three processes.

Assemble a data set of web pages, typically obtained by web crawling, which collects all the web pages encountered by following all hyperlinks within all web pages for the websites to include in a search.

Create a search index from that data set, with an index entry for every occurrence of every word in each web page. An index entry would include a word together with the web page where that word was found, the location of of that occurence of the word within that web page, and perhaps other context information for that occurrence.

Implement a search algorithm, which responds to a search query from a user by producing an ordered list of web pages relevant to that query, using the search index and factors such as prominence of a web page or other indicators of relevance to that query.

MapReduce could be used in each of these three stages.

For web crawling, the following MapReduce operation could assemble a list of pages to retrieve.

- mapper

Extract all destination pages of hyperlinks in each web page in the data set so far, and produce a key-value pair (“dest”, “page”) for each hyperlink, where dest is the destination of that hyperlink and page is the web page containing that hyperlink.

- reducer

For the reducer call handling all key-value pairs (“dest”, “page”), produce a single key-value pair (“dest”,” )`` .

MapReduce programming could create a search index from a given set of pages, as described below.

For the search algorithm, MapReduce computations could produce measures of relevance for ordering the search results. For example, one indicator of relevance of a page is the number of times that page occurs as a destination of a hyperlink among all web pages in the data set. This indicator assumes that more important websites will likely be destinations of hyperlinks from other website - this was key assumption of Google’s original search algorithm, called PageRank. To compute that indicator, we could use this MapReduce operation.

- mapper

Same mapper as indicated for web crawling above.

- reducer

Receive all key-value pairs (“dest”, “page”) for a particular destination web page dest, and produce a single key-value pair (“dest”, “ct”) where ct is the count of key-value pairs received for dest.

Actually programming the three processes for a web-search engine requires software parsing web pages in order to separate the word contents of a page from the formatting instructions (e.g., HTML markup), and retrieving the destination pages of hyperlinks. Rather than delve into that web-page parsing software here, we will instead explore how to create a search index for text files such as Project Gutenberg books in the following exercises. The same MapReduce algorithm ideas could produce a search index for web pages, if we had parsing software.

We will use book names and line numbers to represent location of a word within a book. This will require adding names and line numbers to the lines of each book we process. For example, in the version mobydick.txt_ln of mobydick.txt with line numbers, the first line of Chapter 1 appears as

mobydick 507 Call me Ishmael. Some years ago--never mind how long

since that line appears as the 507th line of that book file.

Create and test a simple search index by writing a mapper and a reducer described as follows:

- mapper

For each line of input (with name and line number prepended) in a book, produce a key-value pair (“w”, “book ln”) for each word w that appears on that line, where book is the name of that book and ln is the line number for that line.

- reducer

Identity reducer: emit each key-value pair that a reducer receives.

Notes:

Your mapper should first obtain the value book ln from its line, consisting of all characters in that line before the second space. Then, it should enter a loop that finds each word w in that line after that second space and emit a pair with that word w as the key and book ln as the value.

For the reducer, you can use the identity reducer provided for your language.

Instead of applying your code to an entire book, use the Test interface to check it with some small data, e.g., these two lines:

try 1 This is the first line try 2 This is another line``

The expected output for that input is

another try 2 first try 1 is try 1 is try 2 line try 1 line try 2 the try 1 This try 1 This try 2

The keys should appear in sorted order in the test output, but the values might not be sorted. For example,

line try 2might appear before

line try 1in the test output.

Now try your mapper and reducer from the previous problem with the Project Gutenberg book

mobydick.txt_loc.Here are some ideas for partially checking the results.

Choose a word w that appears in the output of your word-count code on

mobydick.txt(without the file-name and line-number prefixes). Then verify that the word count for w agrees with the number of lines for w in your search-index output. Repeat this verification for multiple words.Choose a word w with a small word count in

mobydick.txt, and check the your search-index results manually for that word. This will involve searching for that word in the filemobydick.txt_loc, perhaps using an editor.

Note:

You can examine the output of a successful WMR job by scrolling in the

Job Succeededpage.Alternatively, you can retrieve the output from a job named

jobnameby downloading from the data path/user/wmr/out/jobname/000000/within WMR.Now use your mapper and reducer to create a search index for multiple books. The example data set

/shared/gutenberg/loc_set1contains the following prefixed Project Gutenberg books./shared/gutenberg/loc/MobyDick.txt_loc (same as

mobydick.txt_locabove)/shared/gutenberg/loc/WarAndPeace.txt_loc

/shared/gutenberg/loc/CompleteShakespeare.txt_loc

/shared/gutenberg/loc/AnnaKarenina.txt_loc

[A multicycle problem, such as sorting the index? A numerical problem like movie ratings? Develop code for handling HTML for web crawling and page rank??]

Suzanne’s outline:

Talk about web-search in particular, and introduce the notion of the cloud.

Give students an overview of the MapReduce paradigm, and then explain how they can access/play with it.

Talk about WebMapReduce, and give them a link to play with.

Also talk about Amazon EC2 clusters, and how they can run their own MapReduce jobs on those.